I love history. As a result, for several of my jobs over the years, I wound up as the unofficial historian for the organization that employed me.

Should it be surprising, then, that Frank the racing fan also is big-time into racing history? I’m doing a lot of history research for the PA Sprint Series, where I spend much of my time as a volunteer writer/editor/photographer, and I volunteer with the Eastern Museum of Motor Racing, where one can get lost in this great sport’s history.

NASCAR history is another major interest, and since I’m not too crazy about the NASCAR of today, I’m naturally drawn to its history, a lot of which I see as the fan’s golden age. For that reason, I hope to do several stories this season on history-related topics.

Today we start with a personal recollection of one of the best NASCAR races I ever saw, the 1966 Beltsville 200 at the long-gone Beltsville (Originally Baltimore-Washington) Speedway in Maryland. To the memories I’ll add some reflections on why this race excited me like today’s events generally don’t.

Beltsville had opened in 1965 and ran one Grand National (Cup) event that season, with Ned Jarrett taking home the trophy. It scheduled two GN/Cup races for 1966, the first on Wednesday, June 15.

Lifelong buddy Dave Fulton and I were just starting to spread our wings and travel to more distant tracks than the Atlantic Rural Exposition Fairgrounds and Southside Speedway in our native Richmond, Va. In fact, we had just graduated from high school. Sadly, our parents weren’t comfortable with their 17-year-old sons driving up to D.C. and back, but Dave’s father agreed to take us. (More about that trip here)

Dave and I both had summer jobs, and his dad worked as well, so everybody had to get off work before we headed north, which meant our schedule was awfully tight. Today we would never have made it, but I-95 wasn’t quite as overwhelmed back then. We made good time, and we got to the track during qualifying.

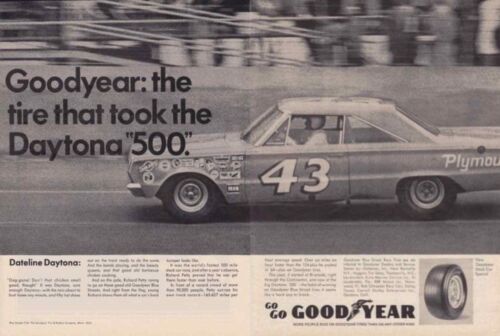

Beltsville was a beautiful track for its day, and maybe that’s why there was a huge field of 31 cars on hand (10 days later, Greenville-Pickens in South Carolina would only draw 18, despite being much more in the middle of stock car country), even with NASCAR’s then-minimum purse of around $5,000 (total!). Remember, too, that this was during Ford’s boycott of NASCAR over allowable engines, so the field included only two factory-backed entries: Richard Petty’s familiar #43 and David Pearson’s Cotton Owens-prepared #6. The other 29 entrants were “independents,” low-buck guys with local body shops as sponsors.

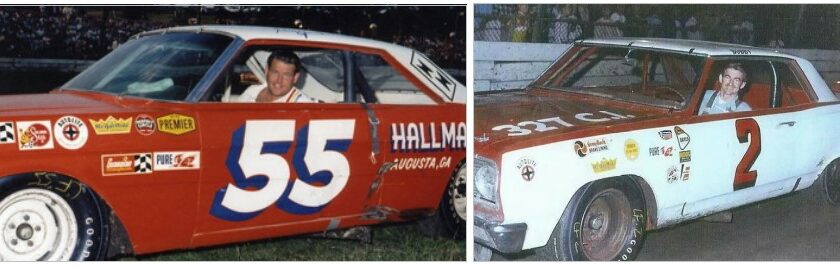

Among them, though, was an odd duck, a base-paint covered Chevy Chevelle with #2 affixed to the doors with adhesive tape. Bobby Allison was the driver.

Now we’re talking about another era of NASCAR rule-making here. Traditionally, Grand National cars had been whatever full-sized vehicle a manufacturer used to lead its line-up, but recent years had brought a new, mid-sized car that fit in between those Impalas and Galaxys and the compact Corvairs and Falcons that had come out several years earlier. (Chrysler Corporation’s Plymouth and Dodge lines were blurring those divides, to NASCAR’s dismay, but that’s another story.)

France hedged his bets and decided to allow the so-called mid-sized cars in, but only with smaller engines (and lower weight limits). The rest of the Beltsville field sported 400-plus cubic-inch engines; Allison had a 327 under his Chevy’s hood.

(Can you imagine NASCAR doing something like that today?)

Things looked predictable at the start. Petty qualified fastest and started on the pole, with Pearson second. Tiger Tom Pistone qualified his fast-but-seldom-around-at-the-finish two-year-old Ford third, followed – surprisingly – by Allison’s little Chevelle. Hometown favorite Elmo Langley was fifth in another aged Ford.

Predictable only lasted until the green flag was thrown, though, as Pearson’s Dodge lost its drive shaft when everybody floored their racers for the start. Suddenly, this looked like Richard Petty’s race.

Petty ran off and hid, building a huge lead that nearly put all but the King’s most ardent fans to sleep, but on lap 71 the blue Plymouth erupted in smoke and coasted to the pits with a blown engine.

Suddenly, things had turned tragic for Petty fans but very interesting for everybody else. Veteran Tiny Lund, famed for winning the 1963 Daytona 500 and operating a fish camp in Cross, S.C., was in the lead (Pistone also was out of the race), with James Hylton and Allison his strongest challengers. Just about everybody else was battling for position a lap or more behind

For 100 laps, Lund and Hylton – a former mechanic who had moved behind the wheel and become one of the most successful of the independents – put a side-by-side show for the lead, while Allison, saving tires and fuel, lurked just behind them.

The finish was shaping up as a three-way nail-biter until Allison dropped out with 26 laps to go, due to differential failure. The little Chevelle had earned the admiration of the crowd, but hearts were divided. Allison had his share, but so did the colorful veteran Lund and the quiet rookie Hylton, who has played a role in the success of NASCAR champions Rex White and Jarrett before switching to driving. “The crowd is on its feet” is a quaint expression, but it was true at Beltsville, and it lasted until the last lap, when Lund took the checkered flag with a winning margin of “two feet.”

It certainly gave Dave and me enough post-mortem topics to make the drive home go a lot quicker. I don’t remember for certain, but Dave’s dad probably took part in the racing equivalent of Monday morning quarterbacking, too.

Look at the race results today, and you’re likely to ask what was the big deal, other than a win for an underdog. Only two cars finished on the lead lap, and half the field had dropped out.

Well, the underdog was certainly a big part of it, especially because the battle involved three underdogs. (Allison wasn’t yet a big name then, and he would score his first two career wins on the old Northern Tour in the weeks to come, then return to Beltsville for #3 in August, when he beat Langley by a lap and Hylton by four, after Petty again blew up while leading.)

The close finish also helped, because with a handful of factory cars so clearly superior to the independents, things sometimes got ridiculously out-of-hand, such as at Spartanburg in 1965, when Jarrett won by 22 laps.

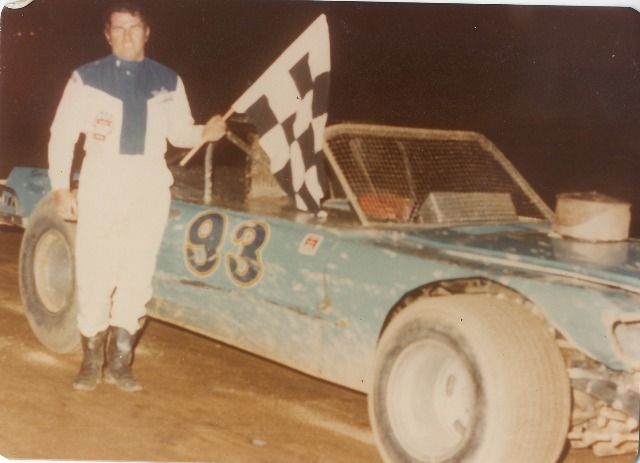

There were underdogs besides the winners, and many had large followings from weekly racing successes. Watt was legendary in Western Pennsylvania, as was Gil Hearne in New Jersey, Sonny Hutchings in Virginia, or third-finishing Hank Thomas at Bowman Gray Stadium

Other drivers just had good stories. Roy Tyner was a Native American whose car said “Wild Indian” over the door. Wendell Scott was African American, fighting against all odds. Worth McMillion was a Virginia alcoholic beverage control agent, enemy of the moonshiners.

This wasn’t a televised race, and fans-in-seats at the track could keep up with battles other than the one for the lead. TV today wouldn’t give a smelly excremental substance, but we knew that Blackie Watt, Jack Lawrence (a/k/a Johnny Wynn from Detroit), and Neil Castles were battling for position toward the rear of the top 10, and it was fun watching them, even if they were eight laps back of the leaders.

That’s how you watch a race.

You never knew if your favorite was going to stay in one piece, either. Witness Pearson and Petty, the two race and fan favorites, both in the garage well before halfway. It added to the fan experience then to expect cars to have engine, differential, clutch, overheating, or oil leak problems.

Finally, it was pretty cheap entertainment. Our tickets probably cost considerably less than ten bucks, maybe only five, and concession prices weren’t outrageous. The gas to get Mr. Fulton’s ’57 Chevy from Richmond to Maryland and back probably was as big an expense as we had.

All right. I couldn’t resist the rant, but it’s only because this was so memorable a race, for reasons that largely play no role in racing today. I’m betting it holds a spot in the memory of attendees much longer than the Clash at the Coliseum will in years to come.

I promise to at least TRY not to bang my better-the-old-way drum too much in future stories like this, and I hope it hasn’t hurt the retelling of this one too badly. If you want, by the way, you can probably use Google to find Dave’s account of this race, which is much more personal, anecdotal, and probably more interesting. Obviously, it still holds a place in his heart, too.

With any luck, maybe next time we’ll talk about another great, competitive race, which also happened to be the next-to-last event on the old dirt track at the Richmond fairgrounds.

(PHOTO CREDITS – Most of these photos came from Pinterest, eBay, or other sites where they had been copied, leaving me with no idea of their origin. The Beltsville late model shot was from Lost Dirt Tracks on Facebook, which likewise copied it from somewhere else. However, the Latimore Valley photos were taken by the author (me), and the Tiny Lund shot in Daytona victory lane is from Midwest Racing Archives.)

Frank Buhrman

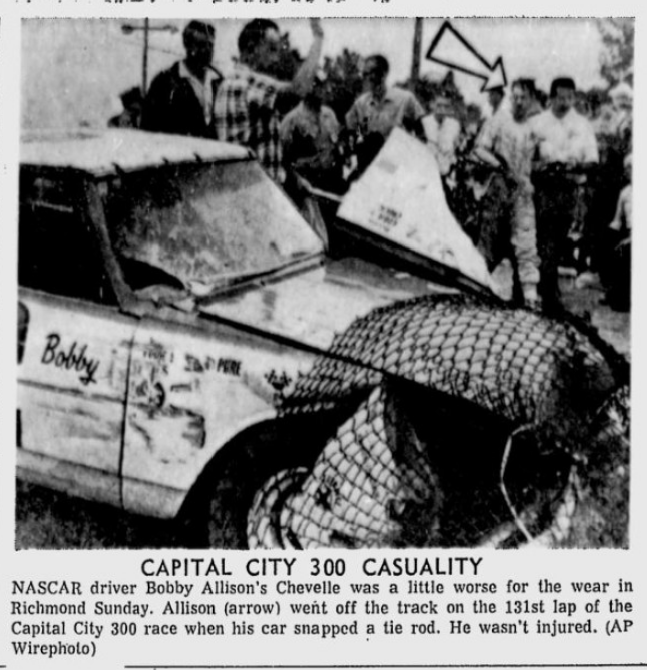

Editor Note: Our friend Dave Fulton sent me this photo of the 1967 Bobby Allison Richmond Fairgrounds crash where he almost landed on wife Judy as referenced by Frank in his comment response on his Beltsville Speedway story below. //B

Thanks for the memories, Frank. This remains my favorite race of the many hundreds I’ve attended through the years.

Loved your story. I saw Bobby in that little Chevelle give Fred Lorenzen and his factory Ford all they wanted at Martinsville later that year. REAL RACIN’

Thanks again

Unfortunately, about 15 months after Beltsville, I saw Bobby flip over the fourth-turn fence at the Richmond fairgrounds and nearly land on the scorers stand, where his wife Judy was just about closest to his car. Scary wreck. I thought the car was junk, but he returned shortly afterward in a Chevelle, which I can’t was the same car or another one. By the time that car phased out, NASCAR was a different place.

As the comment section doesn’t support pictures, so I’ve added a photo that our Friend Dave Fulton sent me about the Bobby Allson crash at Richmond 1967, in a note above.

🏎️ Thanks for the story… my wife found out her Dad raced in NASCAR, just this year. This was Joe Holder’s third and final race for Gene Hobby.

His best finish ever was 20th… but he did beat HOF Wendell Scott two of his three races. 🏁