WARNING: The article below contains NO prescriptions for what ails NASCAR or racing in general, NO explorations of the sport’s past glories, and NO criticism of NASCAR. It contains only memories. Read it at your own risk.

Whenever I read about governments criticizing and attempting to break up “Big Tech,” at some point I mutter, “Don’t mess with Google Images.”

I know it creates copyright nightmares, but I can’t help it. I love being able to look up anything/everything that comes to my mind, then have an array of visual possibilities laid out in front of me. The algorithms aren’t perfect; some of the images are inconceivably miss-selected, but sometimes they hit the nail squarely on the head (something my carpentry un-skills never permit me to do). Over the years with Pure Thunder Racing, Race Fans Forever, and other sites, I have illustrated my writings in ways that wouldn’t have been possible without Google Images.

The one thing it can’t do, though – at least not yet – is retrieve and reproduce images from the mind. I suspect that might be coming, although I likely won’t be around to experience it. That being the case, I’d like to ramble on a bit here and present some mental images that collectively form part of my mental library of racing highlights. If this article hangs around in the dark corners of the Internet long enough, maybe somebody will run it through that mental-images-to-computer-screen process once its perfected.

I don’t need that service, of course, because I can see all these quite clearly in my mind, but in the future, maybe I can share them with you. I’m willing to risk the predominant response being, “Would you look at the time . . . I really have to get going.”

I’ve shared most of these before, but here they are together.

The first image is clearly my first race. I’ve said before that the 1963 Richmond 250 and its extended duel between Joe Weatherly and Junior Johnson made a race fan out of me in a way a less exciting race wouldn’t have done. I can picture the Bud Moore Pontiac #8 and the Ray Fox Chevy #3 side-by-side on the fairgrounds half-mile dirt track, and I can picture Johnson’s Chevy backing through Paul Sawyer’s whitewashed board fence after blowing an engine with less than 10 laps to go. I also can picture my off-white jacket with 250 laps of black tire dust covering it when I got home.

Probably the other race I remember most vividly for the on-track excitement is the 1998 fall race at Richmond, the Exide Batteries NASCAR Select 400, where Jeff Burton and Jeff Gordon waged a battle for the ages in the closing laps. Burton was driving the race sponsor’s car and led more than half the 400 laps, but Gordon was winning everything in those days; he had won six of the previous seven events and would end up with 13 victories and the championship. Nobody thought Burton would be able to hold him off . . . except Jeff Burton, who did just that.

I was working at the track that night and watched the battle on television in the infield media center, so my mental picture is of Burton’s in-car camera showing Gordon’s car alongside.

Two other races are memorable as near-misses. The first took place exactly a year after Burton’s dramatic win and also involved the South Boston, Va., driver. The National Geographic Explorer television program was doing a feature on the race, with Burton as its featured driver, and I was the track’s liaison with the production crew. During the race, Burton was involved in an early incident, and subsequent pit stops dropped him to last in the field. From there he mounted a superhuman, last-to-first charge and dominated the event, until it became apparent that Dale Jarrett had the better car on long runs.

On lap 361 – the same lap Burton had taken the lead a year before – Jarrett was able to get by and go on to victory. Burton finished second. My mental picture is of the crowd going nuts as Burton came down the front stretch after taking the lead in his charge from the rear.

The other near-miss was the spring 2008 race, when Denny Hamlin, even more of a home-town boy than Burton, sat on the pole and lead 381 of the first 382 laps, a level of domination Richmond racing had seldom if ever seen. Then a tire started going down.

My mental picture is of Hamlin intentionally bringing out the caution in a desperate – and less than legal – attempt to preserve that first win at his home track. He was roundly criticized, but I saw it as a perfectly human error, caused when judgment was overruled by the competitive spirit that makes Hamlin Hamlin.

I can’t imagine someone who has never surrendered to an intense core instinct and done the wrong thing.

There are other on-track memories to picture: Lennie Pond leading the World 600 as the ultimate underdog; Danny Dietrich and Brian Monteith exchanging the lead half a dozen times in the last two laps of a sprint car feature at Lincoln Speedway, or Nick Sweigart making an incredible outside pass to go from third to first on the final lap of the Keystone RaceSaver Challenge sprint feature at Port Royal.

But some of the mental pictures aren’t on on-track battles. I can picture Ralph Earnhardt coming over to the fence behind the Richmond pits to talk with three 15-year-olds after his car dropped out of the spring 1964 race, and nearly half a century later, having Danica Patrick call me “Hon” as I opened the door for her after a media session.

I have multiple mental images of Dave Fulton’s and my Greyhound Bus trip from Richmond to Darlington for the 1966 Southern 500: Earl Balmer’s nearly calamitous wreck that nearly brought down the press box (see cover photo); we were at the other end of the grandstand, but that long strip of guard rail lying on the track afterward told just how bad things were.

For two teenagers, though, the experience of the trip also left images: a civic group’s community breakfast in a large hall downtown, and the guy who offered us a ride from the track back to the bus station, then seemed to detour repeatedly to avoid coming close to any law enforcement.

I picture cars: Worth McMillion’s 1965 Grand National Pontiac, with a few handcrafted bits of sheet metal added to make it sort-of look like an eligible ’66 model at Richmond in the spring of ’68 – NASCAR didn’t buy it. I see an Austin Mini Cooper racing with the Camaros and Mustangs at Richmond’s first Grand American (then Grand Touring) race (also the next-to-last race run on the dirt there), and I see a 1966 Chevelle painted to look exactly like Curtis Turner’s Smoky Yunick car but racing in Pennsylvania street stock races half a century later.

I clearly see a pure-stock car burning up completely (with the driver safely out) at Trico (now Orange County) Speedway in North Carolina, when all the fire extinguishers on hand had been used, and the flames came back. By the time the fire trucks arrived, only the tires were still burning, and then it started to rain. The promoter told everybody to get a refund and gave up his job.

I see a car upside down at the Kingsdale VFD Motorsports Arena (a mud bog with a dirt oval carved around it), pink Happy 16th Birthday Mylar balloons tied to a rear roof post, and the driver’s boyfriend climbing out the back window (passengers were allowed). The car was righted and continued to race.

My memory viewer replays traffic pouring into the fairgrounds at Richmond for a mid-‘60s race, with Stick Elliott’s Grand National Chevy dutifully in line as it returned from work done at a garage across the street.

Years later, with NASCAR at its most popular and me finally leaving my infield media center work at about 2:30 a.m., I see my car passing through the infield tunnel and heading up a drive thinly lined with fans – even at that time of night – seeking autographs from those departing. “Not famous,” I yelled.

On the sadder side, I see a group of Richmond Raceway public relations people (including the weekenders like me) calling retired track PR Director Ken Campbell to make sure we were right about the last fatality there. We had watched Jerry Nadeau’s crash and were afraid he had not survived (he had).

Years later, from a race at Williams Grove Speedway in Pennsylvania, I see another crash, this one claiming the life of a young sprint car driver named Billy Kimmel.

If Google’s technology succeeds in reproducing those mental images, I don’t want to look at them. I’d like to erase the ones in my brain, too.

But then I see another facial expression on a Richmond PR staffer’s face. This time it’s not concern and sadness, but rather “my-life-passed-in-front-of-my-eyes” alarm when the new PR director learned that my 15-year-old son (three years younger than required) was running the press box for an IndyCar race. When I need a laugh – which happens a lot these days – I’d like a copy of that one.

Retrieving these mental images could go on and on, like a flip chart with no end, but my audiences have realistic limits, which I’ve probably passed already.

As you can see now, this article has had no real point or direction beyond being a waltz down memory lane by somebody who can’t dance. Sometimes it’s OK to do things that have no greater purpose. If you enjoyed these, that’s reason enough.

I’ll close with two more, both from Richmond in the 1960s, but on either side of the track being paved. The “before” is one of those pictures I’d avoid had it not turned out a lot better than feared. At the fall Capital City 300 in 1967, I was sitting in the fourth turn bleachers when Bobby Allison, driving the revolutionary little Donald Brackins ’65 Chevelle, hit a rut coming out of the fourth turn, broke his right front axle, and flipped into and over the catch-fence. In those days the race scorers, human beings recording flip-clock numbers each time a car passed, were on a concrete slap between the main grandstand and the bleachers – but much closer to the track.

Allison’s car came ever so close to flipping into the crowd of scorers, with his wife Judy at the corner of the group nearest where his came landed.

My mental image is of Allison’s car wrapped in the chain-link fencing it had brought down. It’s an easy image to recall, only because everyone walked away.

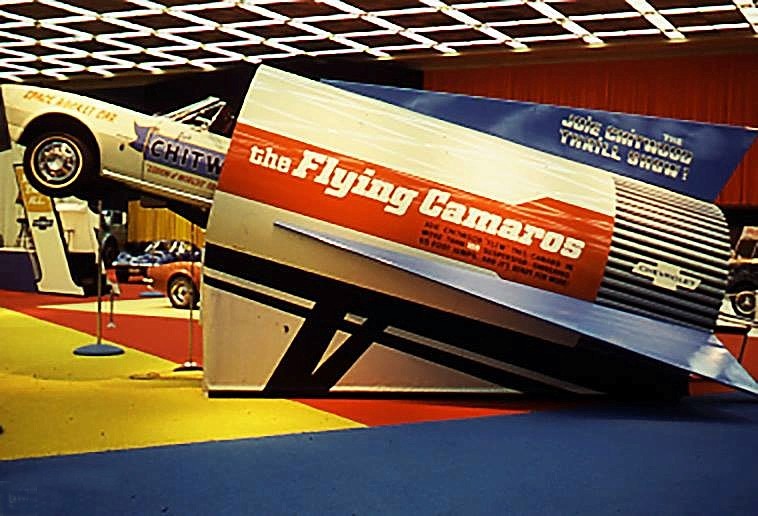

The final picture comes from a bit less than two years later. The track had been paved and named Richmond Fairgrounds Raceway, and NASCAR’s Grand Touring/Grand American Division brought its Camaros, Mustangs and other “pony cars” to town. Among them was a Camaro owned by Joie Chitwood and regularly driven by Joie Chitwood Jr. For this race, though, it would be driven by Richmond legend Ray Hendrick, who would take the normally less-than-frontrunning #67 and put it in the lead . . . until the car broke.

The memory is before any of that. The car was brought to the race on a Chitwood Thrill Show truck, equipped with a vaguely rocket-looking launcher that would blast the car into one of its stunts in a thrill show.

Here it was just for show, except that the giant fin atop the launcher proved too tall for the wiring over the gate that allowed access to the infield. The Chitwood hauler got stuck, and that’s my picture.

Eventually the hauler was backed out of the gate and redirected to the backstretch, where there were no obstacles to crossing.

In a day when haulers weren’t standardized like they are now, it was a little prerace entertainment.

Then as now, entertainment was what we sought. That’s the objective here, too, and I hope you’ve enjoyed the pictures, even though they’re still trapped in my mind and not available to all via a technology that might be with us sooner than we think.

(PHOTO CREDITS – The cover photo of Earl Balmer’s 1966 Darlington wreck comes from NASCAR, although borrowed directly from mikemulhern.net. The Joe Weatherly and Junior Johnson images are ones that have been used all over the place for years. The Weatherly shot, a publicity photo from the beginning, now belongs to Getty Images; the Johnson photo looks like it came from the same initial shoot – probably NASCAR publicity photos by T. Taylor Warren – but in truth I have no idea. The Jeff Burton photo is from NASCAR. The Stick Elliott photo – this is a first for my writing here – is from FindAGrave.com, where it was added by “RM pa” to information about Elliott/Daves’ final resting place. The Chitwood photo is almost certainly a publicity shot, but I can’t be more specific about its origins/ownership than, “it’s out there on the web.”)

Frank Buhrman

So many memories. So many pictures. Happy to have shared some with you. The older I get the more I find myself waltzing (well hobbling) down memory lane. Thanks Frank.

So far, at least, the mind hasn’t been hit with as many limitations as the knees.

Great Story.

Frank, so many memories, so many smiles and so many thoughts…thank you. Our memories are so important and you truly expressed so much to pass down

Please come back soon!

Frank, what a great trip down memory lane. Thanks for sharing. It jarred a few loose of my own… which is much enjoyed and appreciated. Thanks and stay safe!

Great article. Thanks so much for sharing these memories & photo’s. BTW, Stick Elliott was my Stepdad. I didn’t get to see him race much NASCAR, but I grew up at those NC, SC Dirt tracks in the 70’s & until we lost him in 1980.

We slways pulled for “Stick” in the GN races as one of our independent Chevy brigade vs the factory Ford & Chrysler teams.

Thanks for the comment, Tammy. I knew from the pages of Southern Motorsports Journal and Southern MotoRacing that your Stepdad was a great driver on the weekly tracks, but I don’t think I ever had a chance to see him run there, sadly. If only we could have had a Saturday night race prior to Charlotte, Atlanta, or Darlington, at a nearby dirt track, with all the “independents” in cars that more closely matched their skills than the second-tier Grand National equipment they would drive on Sunday. That would be a race worthy of trying to find a time machine to zoom back and watch.